Flood waters, perhaps 300 feet above you, once rushed over these cliffs.

During the ice age, glaciers to the north blocked the Columbia River and forced it to find a new route. The river, swollen from melting glacial ice, began to carve a new channel here. But that was only the beginning.

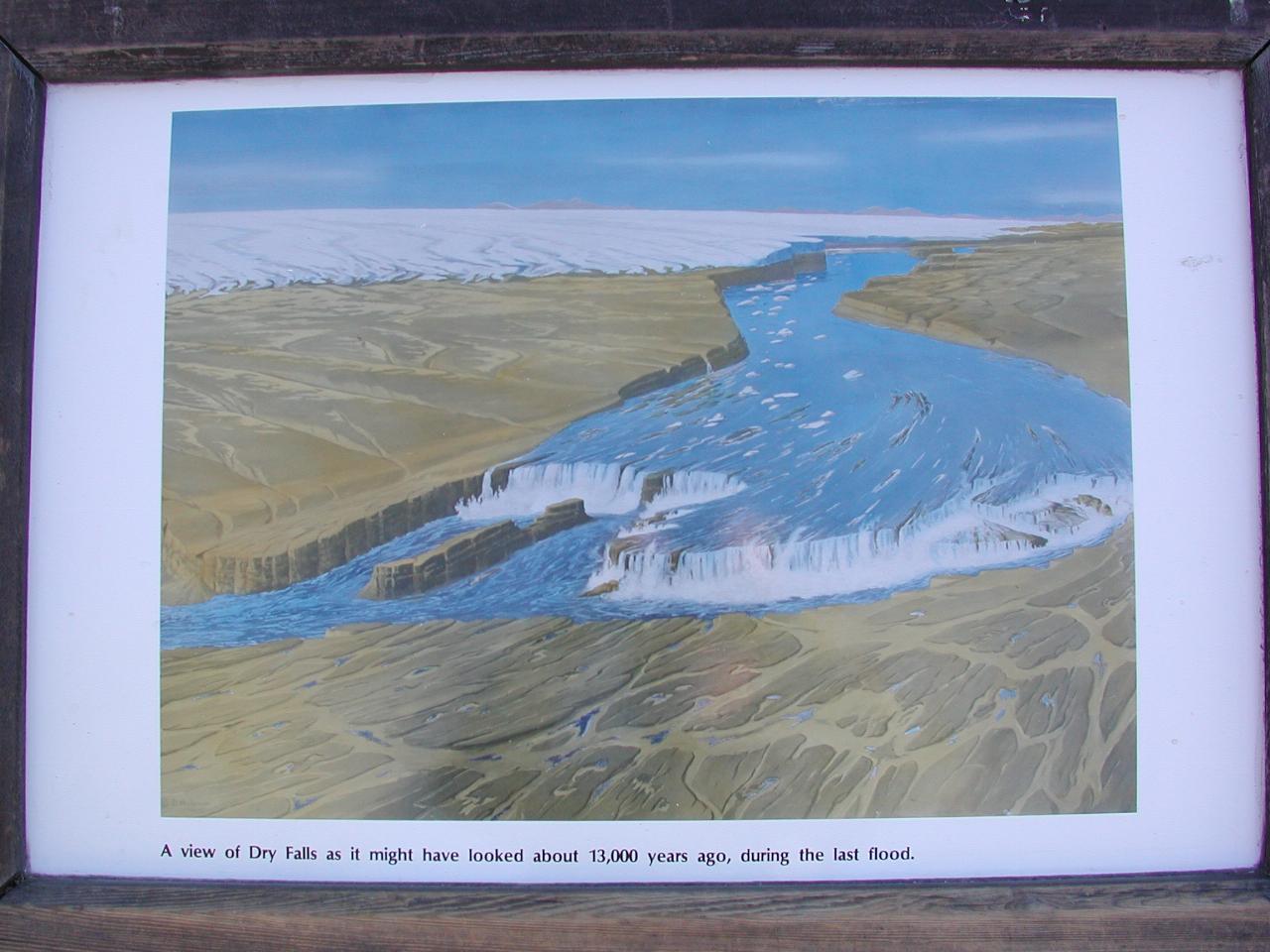

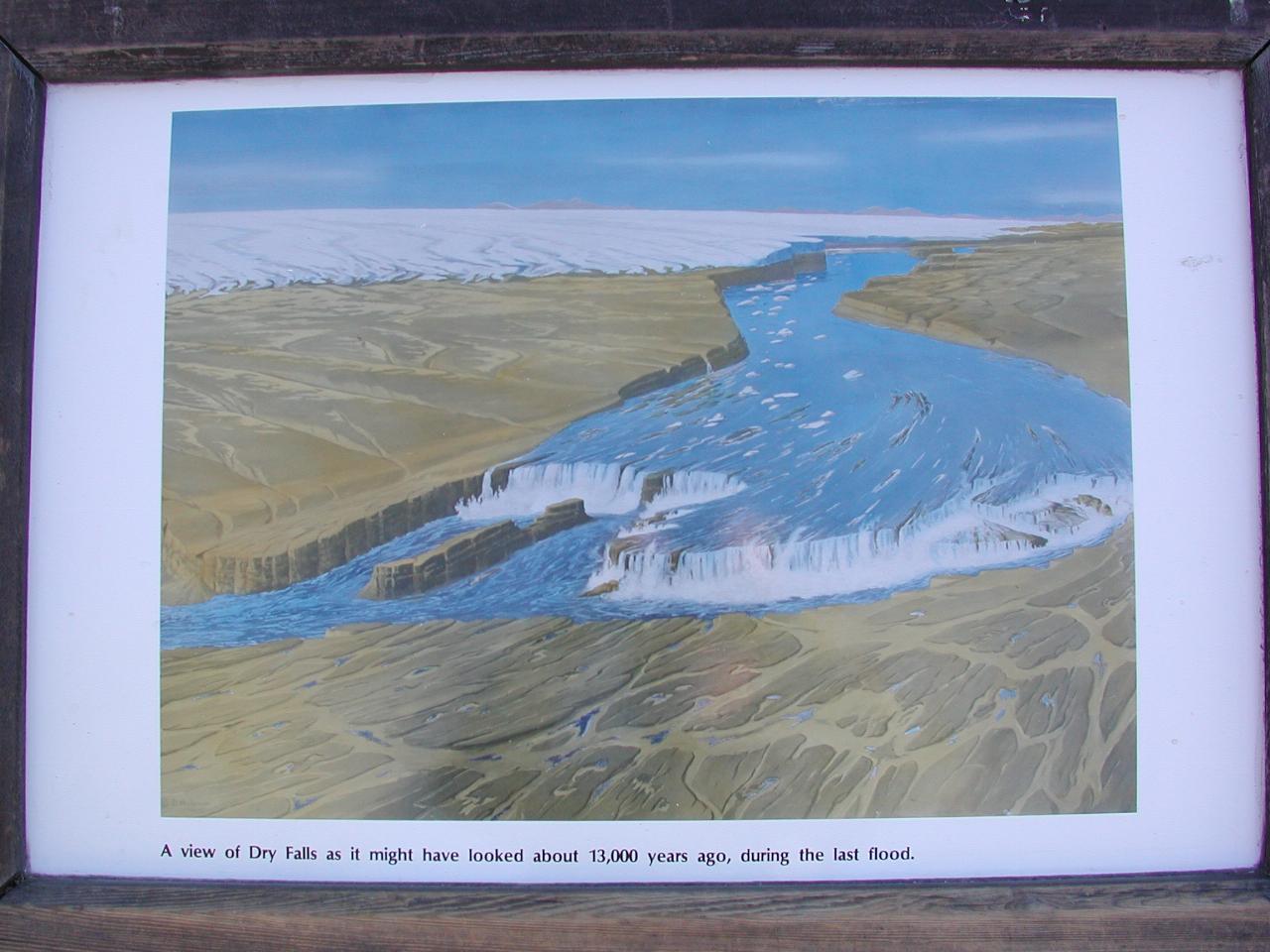

A river in Idaho found no way around its ice dam. The river filled its valley with a huge lake that flooded many square miles of Montana - until the ice dam broke. With a flow up to ten times the combined flow of all rivers of the world, the lake emptied across Idaho and onto eastern Washington. Much of the water rushed through the new channel opened by the Columbia River. The turbulent water enlarged the channel and created huge waterfalls. Eastern Washington was scoured by many such floods, each lasting only a few weeks.

When the last flood subsided, large areas of eastern Washington were left scarred with dry channels, called coulees. This one, the Grand Coulee, is the largest. Cutting across the coulee is Dry Falls. This 3.5 mile wild and over 400 foot tall group of scalloped cliffs was at one time the largest waterfall in the world.

These cliffs are skeletal remnants of what was once the world's largest waterfall. They bear stark witness to the tremendous power of catastrophic floods that swept over eastern Washington at the end of the last ice age.

The falls began 20 miles to the south, but receeded upstream through powerful erosive action. The retreat of the falls gave birth to the canyon below, the Lower Grand Coulee, with the enormous force of the floodwaters spewing several cubic miles of rock over vast areas downstream. Today, Dry Falls remains as one of the most spectacular geological wonders of the age of ice.